THE FIGHT FOR SURVIVAL: WHEN THE GOVERNMENT COMES FOR YOUR CLOSED CASE

A three-part examination of DHS’s mass recalendar campaign and one man’s battle against the system

PART ONE: THE LAW AS WEAPON

The Recalendar Surge Begins

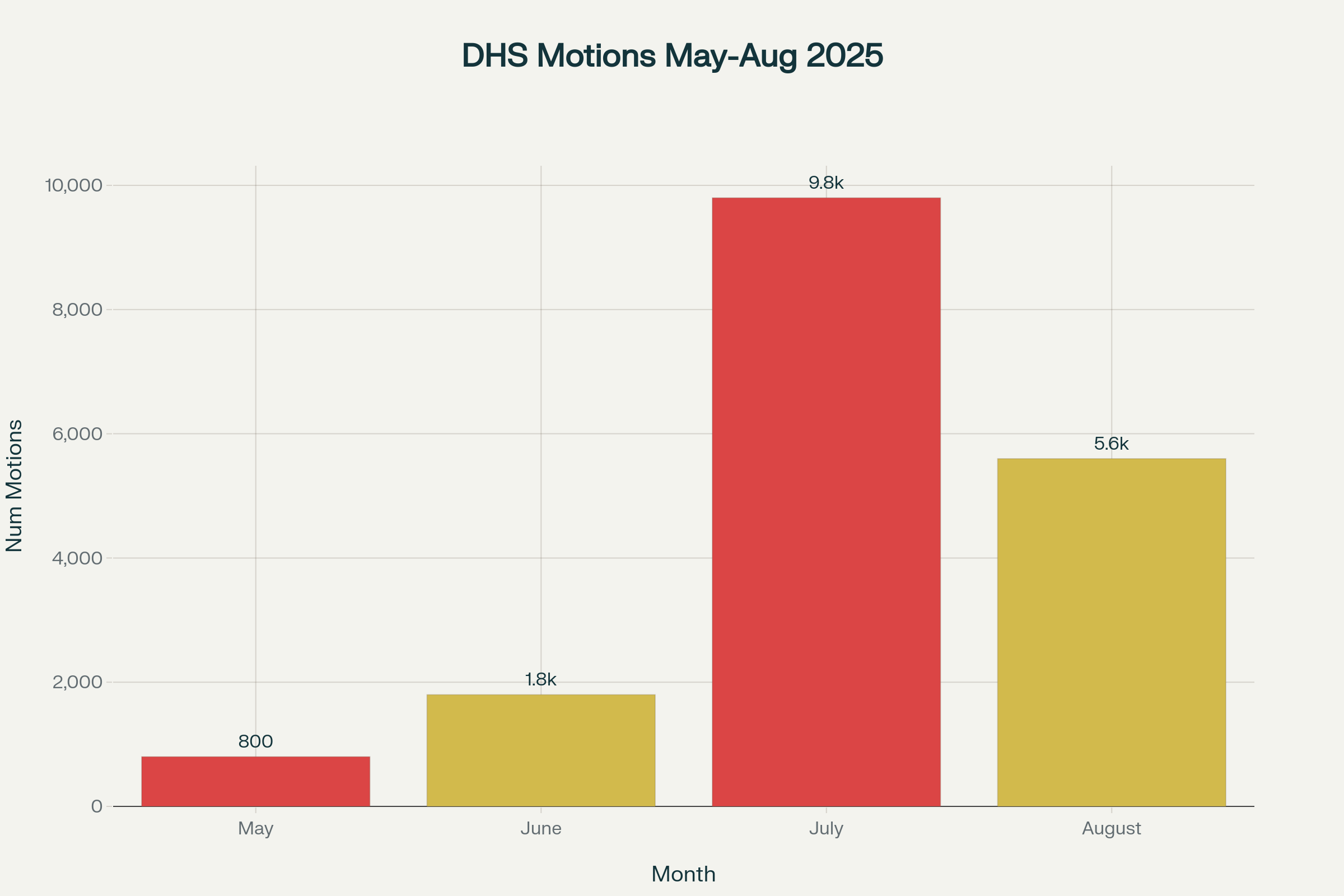

On May 12, 2025, DHS launched a systematic campaign to recalendar thousands of administratively closed immigration cases. Many had been dormant for years, some for over a decade. By July, ICE sent out nearly 10,000 new fine notices; by August, the wave of recalendaring had engulfed courts nationwide.

DHS Enforcement Surge: Timeline May-August 2025

- Motions to recalendar issued in every major jurisdiction

- Surge in reopening long-closed cases, many with complex family and hardship factors

The Eight-Factor Battleground

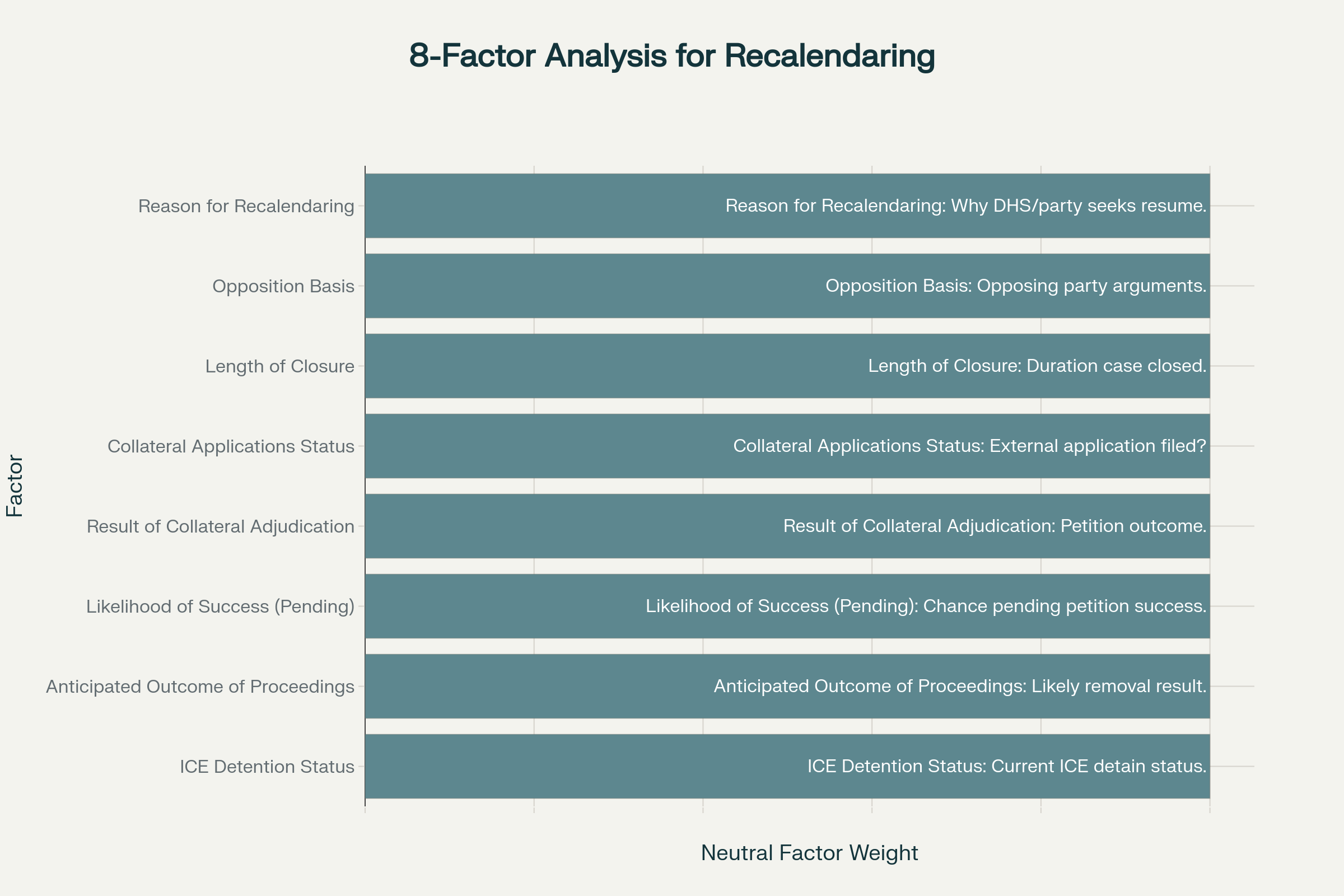

8 CFR §§ 1003.18(c) and 1003.1(l) set out the supposed protections: eight distinct factors immigration judges must weigh before granting any motion to recalendar. These include:

- Reason for recalendaring

- Basis for opposition

- Length of administrative closure

- Status of collateral applications

- Results of application adjudication

- Likelihood of success on pending applications

- Anticipated outcome if proceedings restart

- ICE detention status

No single factor dominates: the law requires a “totality of circumstances” analysis. Yet, DHS routinely files template motions that treat these critical safeguards as mere suggestions, ignoring the actual lives on the line.

The Stop-Time Revolution

Two Supreme Court decisions changed the game for many:

Pereira v. Sessions (2018) and Niz-Chavez v. Garland (2021) held that defective Notices to Appear (NTAs) — those lacking specific time, date, and place — don’t trigger the “stop-time” rule for cancellation of removal. For thousands, this technical ruling means their clock for qualifying relief never stopped running. Immigrants who were ineligible years ago are now suddenly eligible for relief thanks to a paperwork oversight.

Source: VisaVerge

Matter of B-N-K- vs. Reality

Despite the regulation, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) tried to elevate “persuasive reasons for a case to proceed on the merits” above all else via Matter of B-N-K-. This contradicts the Administrative Closure Final Rule: judges must consider all factors, not just government preferences or expediency.

Source: ILRC Practice Advisory

Procedural Warfare

Most recent DHS recalendaring motions openly flout procedural standards:

- No good faith “meet and confer” attempts

- Deficient or defective service (mismatched postmarks and proofs)

- Missed or improper signatures

- Recycled, erroneous case info

- Generic, non-individualized arguments

A few courts push back, rejecting template filings; others allow them, fueling deeply inconsistent nationwide standards.

The Four Response Strategies

- Motion to Extend Response Time: Use procedural flaws to delay and strengthen your substantive challenge, especially with the near-impossible 10-day response window and snail mail service.

- Strategic Non-Opposition: When recalendaring means the client now qualifies for valuable relief (like cancellation of removal), returning to active court can serve their interests.

- Termination of Proceedings: Under 2024 regs, many cases meet the bar for permanent termination—not just closure. If successful, the case isn’t simply “paused” but ended unless DHS re-files charges.

- Total Opposition: In all cases where reopening puts clients at risk, document every procedural and due process violation; force the judge to honestly follow the eight-factor framework.

PART TWO: THE POLITICS OF CRUELTY

The Human Toll of Bureaucratized Enforcement

Numbers reveal only part of the suffering. In Chicago, over 193,000 pending immigration cases rank it as the nation’s fifth most backlogged court.

Source: CBP Monthly Update

Yet the administration has slashed staffing: more than 103 judges fired or resigned. Chicago’s immigration court, intended for significantly more judges, now operates with only a handful—exacerbating already massive delays. Hearings scheduled as far out as 2029 have become the norm, while detained immigrants typically wait 3-6 months before their first court appearance..

Source: NBC Data

Economic Terrorism, Bureaucracy-as-Weapon

Despite <$170 billion in funding> and a congressional mandate to grow the system, ICE detention hit an all-time high of 56,945 people as of July 2025—71.1% with no criminal record. The pretext of “targeting criminals” is a myth; the reality is mass detention of families, workers, and vulnerable survivors.

Source: Immigration Issues

Arrested at the Courthouse Door

In a chilling new twist, EOIR lifted bans on courthouse arrests. ICE now detains people the moment their cases are terminated, turning courthouses into ambush sites. Attorneys describe watching their clients leave court victorious, only to be snatched by ICE moments later.

Source: TRAC Reports

Representation in Crisis

Only one in four immigrants in Chicago’s courts has a lawyer. Nationally, the number is barely one in three. Representation makes a massive difference: five-times higher success rates for those with counsel. But the combination of soaring backlogs, remote detention, and system hostility cripples access to justice.

Source: TRAC Reports

Expedited Removal: The Ignorance Gambit

The nationwide expansion of expedited removal means any noncitizen unable to prove two years continuous presence is at risk of summary ejection—no hearing, no judge, no lawyer. Most don’t even realize they must claim fear of return to get a real hearing, making ignorance itself a tool for government speed.

Constitutional Challenges Emerge

The mass recalendar campaign raises deep constitutional concerns—from due process violations to equal protection, from arbitrary enforcement to family separation without compelling cause.

Chicago Sanctuary City Status Upheld: July 2025

Case Name: State of Illinois v. City of Chicago

Date Decided: July 2025

Court: U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois

Judge Jenkins reaffirmed that local and state governments cannot be forced to participate in federal immigration enforcement, as this would violate constitutional principles of state sovereignty and federalism. She also clarified that the federal government did not suffer a direct, individual injury from the policies and, therefore, lacked the legal basis to sue. The ruling applies the Tenth Amendment to protect local autonomy and makes clear that federal law cannot commandeer states to enforce federal regulatory programs.

“The Sanctuary Policies reflect Defendants’ decision not to engage in enforcing civil immigration law—a choice protected by the Tenth Amendment and not overridden by the [Immigration and Nationality Act]… Finding that these same Policy provisions constitute discrimination or impermissible regulation would provide an end-run around the Tenth Amendment. It would allow the federal government to commandeer States under the guise of intergovernmental immunity—the exact type of direct regulation of states barred by the Tenth Amendment.”

Key Points of the Ruling

- The U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois dismissed the federal government’s lawsuit against Illinois, Cook County, and Chicago, allowing Chicago’s sanctuary city policies to remain intact. The court finds that the Department of Justice lacks standing to challenge these policies or force city officials to cooperate with federal immigration enforcement beyond existing.

- The decision protects local access to city services regardless of immigration status, and bars city employees from inquiring about immigration status except as required by law. “Standing” refers to the legal right to bring a lawsuit. To have standing in federal court, the plaintiff must show that the challenged action causes them a concrete and specific injury that the court can address. In this case, the judge determines that the federal government does not suffer a direct, personal harm from Chicago’s sanctuary city policies. The court rules that the Department of Justice cannot claim injury simply because Chicago or Illinois chooses not to assist with federal immigration enforcement in ways not required by law. Because the federal government cannot show a tangible injury from the sanctuary policies, the lawsuit cannot proceed. As a result, the judge dismisses the case, rather than ruling on the substance or legality of the sanctuary city policies themselves.

Impact on Chicago Residents

- Immigrant families retain full access to city services, schools, and healthcare facilities.

- Law enforcement in Chicago continues prioritizing public safety and community trust, not immigration enforcement.

- Legal advocates praise the decision as a major victory for civil rights and local control.

Official Statement

“Chicago will remain a sanctuary city. Our priorities are public safety and community wellbeing—not federal immigration enforcement.”

– Mayor of Chicago, July 2025

PART THREE: JUAN CARLOS—THE AMERICAN DREAM ON TRIAL

The Face of Bureaucratic Terror

Juan Carlos Mendoza begins his day in his Pilsen office, staring at the DHS motion that could destroy everything he built. He arrived at seventeen—alone, bereaved, fleeing a future with nothing in Mexico. By 2012, he had founded J.C. Landscaping, built a regular client base, and bought a home with his U.S. citizen partner who became his spouse, Miguel.

Love in the Time of DOMA

Their story is one of hope through struggle: from learning English via telenovelas, to building a business with nothing but drive, to navigating marriage after DOMA fell and Illinois finally recognized same-sex unions.

Thirteen Years of Security—Now at Risk

Juan Carlos’s case was administratively closed in 2012 due to prosecutorial discretion. He became deeply woven into his community—expanding his business, hiring six employees, coaching soccer, and paying taxes. Thirteen years pass in peaceful, productive work.

Administrative Closure: A History of Executive Discretion and Judicial Authority

Administrative closure has served as a critical docket management tool in immigration courts for decades, representing a complex interplay between executive discretion and judicial authority that has evolved significantly across presidential administrations. Under the Obama Administration, administrative closure became a cornerstone of immigration policy, used extensively as an exercise of prosecutorial discretion to prioritize enforcement resources. Beginning in 2012, the Obama administration implemented systematic prosecutorial discretion policies that allowed Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) attorneys and immigration judges to administratively close cases involving individuals deemed “low priority” for removal—including those with U.S. citizen children, victims of domestic violence, and longtime residents with strong community ties. This approach reflected the administration’s judgment that limited enforcement resources should focus on individuals who posed public safety or national security threats, rather than pursuing removal against all removable noncitizens indiscriminately. Key guidance documents included the John Morton ICE Director Memo on “Exercising Prosecutorial Discretion Consistent with the Civil Immigration Enforcement Priorities” (June 17, 2011) and the DHS Secretary Janet Napolitano Memo on “Exercising Prosecutorial Discretion with Respect to Individuals Who Came to the United States as Children” (June 15, 2012).

The landmark Board of Immigration Appeals decision in Matter of Avetisyan (2012) formalized this discretionary authority, establishing for the first time that immigration judges could unilaterally administratively close cases even over government objection, using a multi-factor analysis that considered equitable circumstances. This represented a significant expansion of judicial discretion, allowing judges to exercise their own judgment about case management and the appropriate use of court resources. Between 2012 and early 2017, approximately 88,249 cases were administratively closed through prosecutorial discretion, effectively removing low-priority cases from overcrowded court dockets and allowing individuals to remain in the United States while maintaining work authorization through pending applications.

The Trump Administration fundamentally reversed this approach, viewing administrative closure as an impediment to enforcement rather than a tool of smart resource allocation. In May 2018, Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued Matter of Castro-Tum, which stripped immigration judges and the Board of Immigration Appeals of their general authority to administratively close cases, arguing that such discretion improperly interfered with DHS prosecutorial decisions. This decision reflected the Trump administration’s judgment that all removable noncitizens should face expedited removal proceedings regardless of equitable factors or enforcement priorities. ICE subsequently moved to recalendar over 355,000 previously closed cases, dramatically expanding the immigration court backlog and forcing individuals who had been living legally with work authorization back into active removal proceedings.

Under the Biden Administration, the pendulum swung back toward embracing administrative closure as both a docket management tool and mechanism for prosecutorial discretion. In July 2021, Attorney General Merrick Garland issued Matter of Cruz-Valdez, which overturned Castro-Tum and restored immigration judges’ authority to administratively close cases using the Avetisyan factors. The Biden administration’s approach represents a return to the judgment that immigration courts function most effectively when judges have discretion to manage their dockets according to case-specific circumstances, enforcement priorities, and equitable considerations. New regulations finalized in 2024 codified administrative closure authority, making it more difficult for future administrations to eliminate this discretionary tool through policy changes alone. The administration also issued comprehensive prosecutorial discretion guidance through the DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas Memo on “Guidelines for the Enforcement of Civil Immigration Law” (September 30, 2021) and the ICE Principal Legal Advisor Kerry Doyle Memo on enforcement guidance (April 3, 2022).

See EOIR Memorandum on Administrative Closure (Nov. 22, 2021).

Read the Official EOIR Memo (PDF)

However, the current Trump Administration’s 2025 recalendaring campaign represents yet another dramatic shift, with DHS filing thousands of motions to recalendar administratively closed cases—including some that have been dormant for decades. This systematic approach to reviving dormant cases reflects the administration’s judgment that administrative closure constitutes an improper “de facto amnesty program” rather than legitimate prosecutorial discretion, prioritizing case resolution over individualized equity determinations and resource allocation considerations that have historically guided immigration enforcement.

The Government Letter

On a random Tuesday, Miguel delivers the DHS motion to recalendar—fear and uncertainty return overnight. This is “bureaucratic terrorism” in practice: just numbers on a spreadsheet to DHS, but lives and families hanging in the balance.

The Legal Reality

Juan Carlos’s opposition is a clinic in the eight-factor analysis:

- Generic government interest: insufficient

- Deep community ties, approved family petition, business contributions

- thirteen years of closure—settled expectations, reliance interests

- Approved I-130, strong grounds for adjustment

- Not detained, integrated into local economy

His NTA, like many, is defective—missing key details—so his clock for cancellation relief never stopped. With over twenty years of continuous presence, he passes every statutory hurdle.

Source: VisaVerge

Exceptional and Extremely Unusual Hardship

The hardship analysis centers on Miguel, Juan Carlos’s U.S. citizen spouse. Matter of Monreal requires hardship “substantially beyond that which would ordinarily be expected to result from the alien’s deportation”.

Source: TRAC Reports

- Economic devastation: Juan Carlos built their business from nothing. Miguel works at the Cultural Center for $35,000 annually. The landscaping business generates $180,000 in revenue. Without Juan Carlos, the business fails and their mortgage defaults.

- Medical hardship: Miguel has Type 1 diabetes requiring expensive medication and regular monitoring. Juan Carlos manages his care, insurance, and medical appointments. Separation would threaten Miguel’s health.

- Social isolation: Miguel’s family accepted their relationship only gradually. Juan Carlos became his primary emotional support. His removal would isolate Miguel from the Latino community they’ve built together.

- Cultural barriers: Miguel speaks limited Spanish and has never lived in Mexico. Following Juan Carlos would mean abandoning his career, his community, and his medical care system.

The Business That Built a Community

J.C. Landscaping employs six people, all immigrants, all supporting families. The business maintains forty-seven properties, mostly for middle-class families in Pilsen, Little Village, and Bridgeport. Juan Carlos charges fair prices and provides reliable service that larger companies won’t match in these neighborhoods.

The employees include Maria, whose son just started high school; Roberto, saving money to bring his wife from Guatemala; and David, a DACA recipient studying business at UIC. If Juan Carlos is deported, six families lose their primary income.

The Weight of the American Dream

Juan Carlos feels the weight differently now. At seventeen, crossing the desert, he carried only hope and fear. Now he carries the dreams of six employees, the expectations of forty-seven clients, the mortgage on a two-flat, and the promise he made to Miguel at City Hall eleven years ago.

The Night Before the Hearing

Juan Carlos and Miguel have a restless night, haunted by the possibility of losing everything because of a bureaucratic decision. Their fight is personal, but it resonates with many others.

The Morning of Truth

Thirty-seven pages of compelling evidence: financial records, medical documentation, employee affidavits, proof of community roots. The legal strategy is airtight, but the system is broken. The battle is between hope and a government machine programmed for attrition.

As of publication, Juan Carlos waits for his verdict. He is not alone. Their business continues; Miguel manages his health. Their employees come to work, but they all wonder what tomorrow will bring.

Strategic Options for Respondents with Pending I-601A Waiver Cases: Carlos’ Path

For individuals like Carlos, whose removal proceedings are being targeted for recalendaring and who have a pending I-601A provisional waiver (with a USCIS receipt), recent practice advisories outline two clear, fact-based legal avenues:

1. Seek Termination of Proceedings and Consular Process Abroad

Overview:

Carlos may request that the Immigration Judge terminate his removal case based on his pending I-601A waiver and any other relevant grounds.

- Benefits:

- Allows Carlos to complete his waiver application with USCIS and, if approved, proceed to consular processing for his immigrant visa abroad.

- The process before USCIS is generally faster, more predictable, and avoids EOIR court backlog and delays.

- Risks/Considerations:

- If departing the United States for consular processing, Carlos must ensure his I-601A is approved. If denied, he may face significant reentry bars.

- Must assess the risk of expedited removal should his case be terminated while the waiver is pending.

- All required evidence (USCIS receipt, supporting documents) must be prepared and presented with the motion to terminate.

- Best Practice: File a motion to terminate removal proceedings, attach the I-601A receipt and support, and clearly explain why termination is preferable. Counsel Carlos about risks and process before making this decision.

Termination of Proceedings (Permanent Case End):

Under regulations effective July 29, 2024 (8 CFR §1003.18(d)), immigration judges and the Board of Immigration Appeals can now end—not just pause—removal cases in several specific scenarios. When a case is terminated, it is completely closed and cannot be restored unless the Department of Homeland Security files new charges. This is a more decisive outcome than administrative closure, which merely suspends a case until further notice.

Mandatory termination applies if:

– No charge of removability can be proven,

– The noncitizen obtains citizenship or qualifying legal status (LPR, asylee, refugee, or designated survivor/trafficking visas),

– Mental incompetency renders a fair hearing impossible,

– Both parties jointly move for termination, or other legal requirements (like NACARA adjustment, see 8 CFR §1245.13(l)) are met.

Judges also have discretionary authority to terminate cases in selected additional circumstances based on a full review of the record, and DHS no longer has unilateral veto power over this relief.

Regulatory authority: 8 CFR §1003.18(d) (July 2024); see ILRC Practice Advisory, ilrc.org/resources/seeking-administrative-closure-and-termination-using-new-eoir-regulations-hostile.

Sample Language for Motion to Terminate (for Carlos):

“Respondent has a pending I-601A provisional waiver (receipt attached). In light of these circumstances, termination of proceedings will allow the respondent to pursue consular processing following waiver approval, avoiding unnecessary delay and hardship associated with backlogged removal proceedings.”

Law on Motions to Terminate Removal Proceedings

- Motions to terminate are governed by 8 CFR §§ 1003.18(d) and 1003.1(m).

- Termination ends removal proceedings entirely; a new Notice to Appear (NTA) is required to bring someone back into court.

- Mandatory termination: The immigration judge must terminate proceedings in specific situations set out in the regulations, such as lack of jurisdiction, ineligible charging documents, granted relief (e.g. U visa, TPS, DACA, SIJ, DALE), or other qualifying status.

- Discretionary termination: Even if mandatory grounds do not apply, the judge may terminate in the exercise of discretion—for instance, where law or circumstances justify resolving the case without further proceedings.

- The motion should identify all relevant mandatory and discretionary grounds, and include documentary evidence supporting those grounds (e.g. grant notices, proof of pending application, deferred action approval).

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE

EXECUTIVE OFFICE FOR IMMIGRATION REVIEW

IMMIGRATION COURT [CITY, STATE]

| In the Matter of: | [Respondent Full Name] |

| Alien Number: | A#[XXXXXXXX] |

| File No: | [XXXXXXXX] |

Motion to Terminate Removal Proceedings

- The Respondent is the beneficiary of and/or has a pending application for [describe relief, e.g., U or T visa, TPS, Deferred Action].

- The basis for previous administrative closure has now been codified as a basis for termination under current EOIR regulations.

- [Summarize factual basis and eligibility for mandatory/discretionary termination. List supporting documents if applicable.]

[Attorney Name]

[Attorney Bar Number]

[Attorney Address]

[Attorney Phone and Email]

Date: [MM/DD/YYYY]

2. Recalendar and Continue Proceedings in Immigration Court

Overview:

Carlos may allow his case to be recalendared and proceed in Immigration Court while his I-601A remains pending.

- Benefits:

- He can ask the judge for administrative closure or continuance pending adjudication of the I-601A.

- If the waiver is approved, he may move for termination or explore other forms of relief.

- Risks/Considerations:

- Court dockets are extremely backlogged; this route may result in prolonged delays.

- Delays may affect eligibility for other forms of relief.

- The process is less predictable and can create stress and disruption for Carlos and his family.

- Best Practice: If Carlos decides to proceed in court, immediately file a motion for continuance or closure, citing the docket backlog and hardship. Document all relevant factors, including the pending I-601A and related hardship.

Summary Table: Carlos’ Two Main Paths

| Option | Pros | Cons/Risks | Key Action Step |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terminate & Consular Process (I-601A) | Court case finished; more predictable with USCIS | Risk at consulate if waiver denied; brief separation; risk of expedited removal if terminated before approval | Motion to terminate with evidence |

| Continue in Immigration Court | May pursue other relief; possibly more options | Significant delays, added stress/costs | Motion to continue/close, monitor case |

Practical Advice for Counsel

- Clearly discuss strategic options, risks, and timelines with Carlos before deciding a path.

- Ensure the court has all updated paperwork, including the I-601A receipt, address, and attorney contact information.

- If pursuing termination, reference why Immigration Court would not efficiently resolve Carlos’ case compared to consular processing.

- If remaining in proceedings, advocate for closure or continuance to minimize time in court.

This guidance integrates the latest practice advisories, providing concrete steps and options for respondents facing recalendaring of closed cases with a pending I-601A waiver.

How Democracy Dies

The slow suffocation of individual hope is not dramatic; it’s procedural, technical, cloaked in the language of “efficiency.” Juan Carlos’s case will decide more than his own fate: it is a proxy for thousands buckling under the weight of government indifference.

The law provides a weapon. Justice insists he should win. But success in Trump’s America demands surviving a system built to grind hope into dust.

Advocacy Takeaways & Resources

- Know your rights: The eight-factor analysis is not optional. Demand individualized consideration, and document every procedural flaw.

- Use Supreme Court decisions: Pereira and Niz-Chavez empower many clients to challenge defective NTAs and seek cancellation relief.

- Oppose template motions aggressively: Challenge DHS’s generic filings with detailed facts, individualized hardship arguments, and requests for procedural fairness.

- Community support: Build and represent not just individuals, but the families, businesses, and communities they sustain.

- Stay updated: Follow the court staffing crisis. Advocate for expanded representation and due process at every step.

- Risk assessment: Understand the real dangers of expedited removal, and advise clients on asserting their rights at first contact.

- ILRC Practice Advisory

- Block Club Chicago: Trump And DOJ Reshape Immigration Court

- Visa Verge: DHS Reopens Deportation Cases Shelved Under Biden

- CBP: National Media Release

- NBC News Immigration Tracker

- Immigration Issues

- TRAC Reports: Court Backlog Data

- NPR: Inside Understaffed Immigration Courts

- WTTW: Trump Administration Fires Immigration Judges

- Matter of Aguilar Hernandez: Defective NTAs

- American Immigration Council: Strategies After Niz-Chavez

- Matter of Monreal: BIA Decision on Exceptional Hardship Standard

Matter of Monreal: “Extreme and Exceptional Hardship” Requirements

- The qualifying relative must suffer hardship substantially beyond that ordinarily expected from deportation.

- Relevant factors include the age, health, family ties, and financial impact on the qualifying relative.

- Social, cultural, and psychological impact must be considered, especially the conditions in the country of relocation.

- Evidence of medical needs, educational disruption, or inability to provide care in the country of relocation weighs in favor of hardship.

- Hardship must be assessed cumulatively and include all relevant circumstances. No single factor is dispositive.

Share this blog. Stand up for every Juan Carlos. Remind America of its promise: justice, redemption, and the dignity of hard work.